|

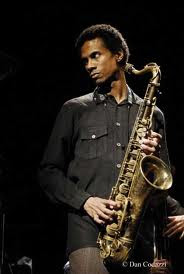

| Gary Bartz |

My first real gig as a New Yorker was with Gary Bartz. In the late 80's and early 90's, I would go to listen to Bartz play at jazz clubs like The Closet and The New Haven Lounge in Baltimore, and the One Step Down and Twins in Washington D.C. So in 1994, when Bartz needed a sub in the piano chair, I already knew his repertoire, and I knew what he liked to hear from his accompanists (Baltimore- based pianist Bob Butta was a longtime associate of Bartz, and a huge influence on my piano playing). Soon after, when Bartz had a gig at Sweet Basil's in New York City, I got the call to join his band. As a member of the Gary Bartz Quartet, I got to record with him on his second album for the Atlantic label called "The Blue Chronicles: Tales Of Life". It was an unforgettable experience and one of the highlights of my career.

I think Gary Bartz is one of those artists like trumpeter Woody Shaw, or tenor saxophonist Billy Harper, who are overlooked by writers and historians simply because, during the 1970's, they didn't do the extreme fusion of bands like Mahavishnu Orchestra or Return To Forever. Those who are really in the know have much praise for Bartz, but I think he has been deserving wider recognition for years. He has played with all the greats: Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Art Blakey, McCoy Tyner, Max Roach, etc...Still, like many jazz greats who aren't young prodigies or ancient masters, Bartz doesn't get the critical acclaim he should.

Gary Bartz is a very humorous person; he can tell hilarious stories with a delivery which is reminiscent of master comedians like Richard Pryor or Redd Foxx. But he is also very socially and politically aware of things. There is a CD I picked up recently which shows his political side in detail. It's a remastering of two records, which were then combined on one CD: "Harlem Bush Music-Taifa" and "Harlem Bush Music-Uhuru" both feature a band which Gary led in the 70's called Ntu Troop. (Ntu comes from the African Bantu languages, which is a sub-branch of Niger-Congo languages, the most common being Swahili. According to Bartz' website, "NTU means unity in all things, time and space, living and dead, seen and unseen.) This group consisted of Bartz on alto and soprano saxophones and vocals, Andy Bey on vocals, Juni Booth on acoustic and electric basses, and Harold White on drums. Nat Bettis plays percussion at times. (On most of "Uhuru", Ron Carter substitutes on bass. Not too shabby!)

|

| Malcolm X |

The fact that the two "Harlem Bush Music" records were fused into one CD release could make one assume that both records were originally one studio session, but it seems that this is not the case. But there is a consistency to the sound and the spirit of the entire disc, which makes a complete listen-through totally satisfying. The sonic texture overall is very organic. Even with electric bass, you get a very acoustic, earthy feeling from the entire CD. The intention here is to channel Mother Africa as the basis for everything in jazz: blues, bebop, funk, free jazz, etc...Not to mention the unapologetic activist viewpoints exhibited, especially in songs like "The Vietcong"(This is 1970: the Vietnam War was in full swing, in case you forgot...) and also "The Warrior's Song", a very intense free piece, during which Bartz overdubs himself reading an excerpt from a speech by the Civil Rights Leader Malcolm X:

"I say bluntly that you have had a generation of Africans who actually believed that you could negotiate, negotiate, negotiate and eventually get some kind of independence. But you're getting a new generation that has been growing, right now, and they're beginning to think with their own minds and see that you can't negotiate up on freedom nowadays. If something is yours by right, then fight for it or shut up. If you can't fight for it, then forget it."

Bartz goes on to quote another of his inspirations, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane:

|

| John Coltrane |

"You know, I want to be a force for real good. In other words, I know that there are bad forces, forces put here that bring suffering to others and misery to the world, but I want to be the force which is truly for good."

I find this to be an interesting juxtaposition, which is probably a common inner conflict for revolutionary thinkers: We want change, but do we remain peaceful, or force change by any means necessary? Political messages in music are so rare now that I found this thread of protest in the music to be extremely enlightening.

We think of Bartz as an alto saxophone master. Bartz has claimed in interviews that his main influence was Charlie Parker; however, many of his fans see him as the post-Coltrane alto-and-soprano man. His tone quality is unmistakable; it's very dark and reedy, and Bartz can add a little edge to his tone for emotional effect, but it never sounds harsh. On this collection, he is very unabashedly playing the blues, but Bartz has always been able to mix many elements into a very cohesive improvisational concept. So there will be blues, but some bebop will occur, and also he might surprise you by quoting a few standards, maybe some folk melodies, perhaps some Coltranish saxophonistic vocabulary will jump out. But it's never forced; it always sounds natural.

(I remember when we were recording "The Blues Chronicles", we were doing several takes of a Bartz original entitled "...And He Called Himself A Messenger". On one of the takes, during Bartz' solo, he quoted a sort of obscure song called "Delilah"(that appears on a Clifford Brown/Max Roach record called "Jordu"). It was so unexpectedly beautiful, it worked perfectly with the changes, it was so inspired that people in the studio were looking at each other and laughing in disbelief! Even those who didn't know the tune were enthralled. Sadly, they didn't use that take on the CD. And the funny thing for me was that in the remaining years I worked in Bartz' band, I never heard him quote that song again!)

On "People Dance", Bartz gets into a vibe where he is almost literally talking or laughing with the alto, using micro tonality to get the effect of human speech. And as the clear bandleader, Bartz has always been expert using his saxophone to "set up" the groove of the song, or change the tempo, or even make a segue or transition into another song, as if he is the master storyteller with the village musicians gathering around him to listen.

|

| Andy Bey |

The earthiness of the music here is enhanced by many vocals, a surprising number of them provided by Bartz; "Blue" features him in his "debut as blues pianist and as a blues singer". But without question, the vocal star here is the incomparable Andy Bey; his rich baritone has the slightest vibrato, and when he goes into his upper register, it's even more impassioned. And the alto and voice blend beautifully well. This brings me to the issue of harmony: due to the lack of a "chordal" instrument like piano (with the exception of "Blue") or guitar, you could call this a "chord-less" band. However, there are many implied harmonies, and much of it is pedal point based (meaning one constant bass note and chords moving above it, but always related to the bass). And there is some vocal overdubbing on songs like "Du(Rain)", where some interestingly dissonant counterpoint is created, and "Parted," the story of an enslaved African man separated from his lady, which has vocal harmonies that might remind one of the South African singing group Ladysmith Black Mambazo. The intention here is to get back to the roots of the music, which means omitting the European structural harmonic influences for a moment. Speaking as a pianist, I am fine with it!

Gary Bartz is still out there playing better than ever: These days he is touring with the legendary pianist McCoy Tyner. He also has his own label, OYO Records( Own Your Own! -which refers to the fact that most musicians don't own the rights to their own material. Bartz, ever the revolutionary, is part of the shifting tide of musicians taking the reigns of their own destiny. Additionally, OYO is also a tribe in Nigeria). For more information about Gary Bartz, please go to his website:

And "Harlem Bush Music - Taifa / Uhuru" is available here: