-->

I recently had the good fortune to do a mini-tour with Jim Rotondi, one of the great jazz trumpeters. I have admired his playing since first hearing him in the 90's at Augie's and with the group One For All. Rotondi is trained in the old school; he knows a lot of tunes, is serious about playing changes and swinging. We played some standards that I have not played in a while; we also played some of his originals which were fun as well. After hanging with Rotondi for the week, I decided that it would be great to interview him for jazztruth.

GC: We're here with Jim Rotondi, one of the great trumpet

players in jazz. He's spent many years in NY and is now in Europe, living part

time in Graz, Austria, and where in France?

JR: The city is

called Clermont-Ferrand, it's in the dead center of France, about 3hrs south

of Paris.

GC: Can you tell me, because I know you're from Butte, MT.,

how did you get into music and when did you decide that you wanted to be a jazz

musician?

JR: I grew up as the youngest of five kids and we always

grew up with music in the house. My

mom was a piano teacher and she wanted all

of us to have music lessons, but insisted on not teaching us because she wanted

to separate family and music endeavor. The way it went down in our family was

that my mother was the musical inspiration and my father enforced all the

rules. All of us were strongly encouraged to take piano lessons, and if we

didn't want to take piano lessons, it was kind of a problem. My siblings and I

took piano lessons until about high school. Along the way, we had the option to

take up another instrument if we wanted to. I wanted to be in some kind of

musical group where I was with other people, rather than practicing solo piano.

And that's how I got into the trumpet. I started playing piano at the age of 8

and started the trumpet at12.

Now sort of briefly speaking about the musical community in

Butte, Montana, there really wasn't one. My initial exposure was from public

radio and a buddy of mine in junior high had the Clifford Brown and Max Roach

vinyl set. He was also a trumpet player and he let me take it home for a few

weeks and it completely blew my mind. Any trumpet player that hears Clifford

Brown for the first time, more or less, has to be overwhelmed.

GC: I had the same feeling.

JR: I finished high school and always had the vision to get

the hell out of Montana as soon as possible. You also asked, how did I arrive

at the decision that I wanted to be a jazz musician and make that my life

calling? That didn't happen actually until a few years after graduating high

school. Ironically, my father enforced the rules that we had to take piano

lessons, but when I decided to become a musician, it backfired on him. He

didn't want me to be a professional musician and was upset when I told him I

was going to the University of North Texas to study music. Like most fathers,

he wanted to know that I'll have security.

Anyway, I was hesitant the first two years after high school

when I was in college at U of O in Eugene, OR. I didn't know what I was going

to do, but I was enrolled in a bunch of courses that I was not going to in

favor of practicing the trumpet. I was practicing more than some of the music

majors there and always listening to music with my older brother in our

apartment. I'll never forget, I was listening to an Inner City record of Dexter

Gordon called “Bouncin' with Dex, ” with Billy Higgins and Tete Montoliu. They

were swinging like a mofo and I just looked at my brother and said, “You know

what man, I'm outta here. Next fall I'll be going to a music school.” It

happened like that.

GC: Wow, Interesting. So you went to UNT?

JR: Yep and I graduated with a Bachelor's degree in 1985.

GC: Did you go to NY right after that?

JR: No I didn't. I didn't have any bread. Since my dad was

ambivalent towards me becoming a musician, I made it a point of pride to not

ask him for money. I figured I'm gonna have to do a gig or some kind of job.

North Texas is the kind of institution that is contacted by a lot of

professionals for young student recruits. I got a call from a cruise ship and I

did that for a year to save bread. After that I moved to NY in 1987.

GC: When you got to NY, how did you get started?

JR: I met some contacts on that ship that were really

valuable. One of those contacts was Richie Vitale, a great bebop trumpet player and another guy was a keyboard

player named George Whitty. When I got to NY, I called them as well as a bunch

of other people saying that I'm in town and went to a ton of jam sessions. I

forget who recommended me to go on a tour of an off Broadway show, but it was

an R&B review show happening at the Village Gate. I went and auditioned, got the gig, and within months of

moving to New York, I was on the road. It lasted about 5 months off and on

though. But that was the start of road gigs that got me out of the city til

about 1992. I went on the road with the Artie Shaw Big Band and was called to

do the Ray Charles thing in 1991. Basically, my musical subsistence at that

point was either going on the road or doing wedding/ bar mitzvah type gigs.

GC: So cut to 1991-92, Augie's was happening. Were you on that scene?

JR: Augie's was happening before that, Joe Farnsworth was

giving weekends in 1989. In and around all the things I've been talking about,

I was doing that too. It's an outstanding experience as you know from doing

similar gigs. Joe was visionary with that gig because he could have had just

one steady group every weekend, but he used this opportunity to play with cats

he didn't normally get the chance to play with. It was through this that I met

Junior Cook and Cecil Payne, Charles Davis, and a host of other saxophone players. John Patton and Eddie

Gladden used to come play when Joe couldn't do it.

GC: So, you were going on the road and you would do this?

JR: Yeah, a big point of contention was that Joe wanted me

to reserve my weekends for his gig, but I had wedding gigs and I had to pay my

rent.

GC: Did you feel a difference between playing with Ray

Charles versus a jazz gig at Augie's?

JR: Playing with Ray Charles, for me, was a jazz gig. I was

a featured soloist, and he wanted all of us to play. he had arrangements in his

book that had Trane changes. He actually tested us to see if we had it

together. It was a blowing gig whether you liked it or not. He had a great

book; Quincy Jones, Ernie Wilkins, and all these great cats wrote for him.

GC: How long were you with Ray Charles?

JR: About a year and a half. I did one tour which was 7

months and at the end of it, I did a bunch of stuff with him but was not

officially in the group.

GC: How did One for All get started?

JR: One for All got started through Joe Farnsworth Augie's

thing. It came together piece by piece. Joe and Eric Alexander went to school

at William Patterson. Joe got the gig at Augie's and when he wasn't hiring

other cats, we were doing it as a quintet. John Webber was always on that scene

too and was playing most of those gigs. One for All officially came together

because I got a weekend at Smalls. I had been talking to David Hazeltine. At

the time he was living with Brian Lynch in Chinatown. We all thought that David

and Brian were a package deal because they played a lot with each other, but

Dave started asking us to come over for sessions when Brian was out of town. We

found out Dave had arrangements ready to go for a sextet. Joe knows Steve Davis

because Joe's from Massachusetts and Steve is from Hartford. The whole band

played together for the first time at Small's in 1992 or 93 I think. Then we

tried to doing that sextet all the time. The first time that personnel recorded

was on Steve's album Dig Deep. Six months later we did our first for Sharp

Nine.

GC: What's the status of One for All?

JR: It's harder since I don't live in the US anymore and

it's never been an easy band to book. Eric Alexander skyrocketed in popularity

in 10 yrs. There was some contention that people would perceive it as Eric

Alexander and One for All. We as the group wanted to keep it as a

co-operative, but Eric's other band was working more than we were. I think it's

unfortunate because we could've done a lot more.

GC: At some point you started pursuing teaching gigs and you

won the position at the Graz Conservatory?

JR: I'm going into my fourth year.

GC: Did you think of yourself as an educator?

JR: No, definitely not. The first two jobs I had, I didn't

seek out, they came to me. John Thaddeus and Todd Coolman both sounded me for

an adjunct gig at SUNY Purchase and I was there for 10 years. The year before I

left town, I was on the faculty for Rutgers University. I didn't think of

myself as a teacher but when they asked me to do it, I thought I would try it.

Being a teacher crystallizes what you do because if you can't clearly explain

what to do, then you really don't understand it. I felt like I had to get it

together so I could show students what I was doing and to help them with what

they wanted to do. It took me a minute, but after a while I fell into a groove

for teaching.

GC: how would you describe your way to teaching jazz?

JR: My philosophy about improvising on the trumpet is that it's

a unique study because improvising eliminates the concept of pacing. You don't

know exactly how long you're going to play. When I deal on the technical side

with students, I always talk to them about that. I also tell them think about

things that are substitutes to pacing so they don't blow out their chops right

away. I have exercises that I do that are technical but also can be musical

phrases that deal with harmonic sequence. We work a lot at the keyboard, a lot

of ear training, study language a number of ways such as transcription and

listening.

GC: What strikes me about your playing is that the music

comes through. I think the best jazz musicians transcend the instrument. Have

you always had that?

JR:I wasn't one of those natural guys. There was a period in

my development early on when I was in NY where I sought out specific technical

advice for the problems I was having. For me, it has taken me a while and I was

really fortunate to have some technique oriented teachers that have helped me a

lot. Going back to how I teach, I talk a lot about transcending the physical

difficulty of the instrument and being musical.

GC: I personally am into a lot of different types of music

and now that I teach history, I'm more fascinated with the old and with what

things people consider new but are now technically old. How do address the

notion of musicians or students rejecting the past completely as if it never

happened? What's your opinion?

JR: I think jazz music has always favored innovation but key

principles from the previous generation's music were retained. What you mention, sometimes appears to

be change at the expense of all else. Young people are always going to be

young, they're going to want to

change the world, conquer it, and do their own thing. I dig that and I think

that's very important in young people and that keeps us young. As a teacher, I

don't want to fight that, but rather balance that. My responsibility as an

older musician who knows a bit of that stuff is to get them into what has already

happened.

GC: Do you think Europe will be the center of jazz? Do you

think that NY will lose its claim to being the place that everyone feels like

they need to go?

JR: I do not, and I say that as a European musician now. I

think Europeans have their take on the music which is unique. I'm not sure

there's anything strong enough to lay claim as the capital of music.

GC: I think so too. Some people might say you have to go to

NY or Berlin but another person might not have the same experience.

JR: I still feel like there's an energy in NY that doesn't

exist in any other city.

GC: I totally agree. Especially with the music. Whether

anybody's working or not, when you play with cats from NY, you just feel it

immediately, it's different. It's hard to get that from other places.

JR: When you go back, there's a little bit of a letdown. I

don't want to be hypercritical because I'm in that community. I have a group I

work with now that contains a lot of former students. One of the things I work

with them, especially rhythm section members is maintaining energy. They always

want to have some energy and drop it down, and I don't think that's necessary.

It's more important to maintain an energy level.

GC: What was it like working with Harold Mabern?

JR: Great, [laughs] speaking of energy. He's in his late 70s

now, I guess. I worked with him about a month ago. He has more energy than any

one musician I've ever played with. The qualities I love in him aside from his

energy is his knowledge of material. He taught me a lot of things that I teach

now about harmony and substitutions. He's a selfless mentor.

GC: Do you think knowing tunes is a lost art?

JR: Yes, absolutely.

GC: How do you feel about that?

JR: I don't like it. I think studying tunes like that

informs your ideas on composing. Students want to write tunes without having

studied those song forms and harmonic sequences, and it doesn't work. They

don't know it and they're not qualified yet to write. I can think of a million

reasons to study all that music and not one reason to not study it.

GC: Do you have anything new coming up?

JR: My most recent recording (Hard Hittin' at the Bird's

Eye) came out a few months ago on the Sharp Nine label. I'm hoping to

record my electric group from Austria next fall or spring. I'm excited about

these guys because it's an opportunity for me to write in a new way. It's

different than anything I've done before.

GC: I've already heard this story, and I couldn't stop

laughing. If you can tell the story....

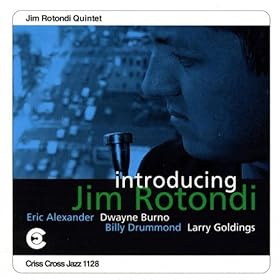

JR: What happened was when I recorded my first album as a

bandleader on the Criss Cross label and it's called Introducing Jim Rotondi.

I guess for some people, my name is not the easiest to pronounce.

GC: Where does your name come from?

JR: It's Italian, my grandfather was from Naples. So, there

was a certain radio DJ in the NY area back in the 90s that had an evening

program. The DJ featured some clips of my album, but he had difficulty

pronouncing my name and would always say, “That's music from brand new artist

Jeb Rodonti.” I hadn't heard it myself, but people kept on telling me that the

DJ was calling me Jeb Rodonti. I listened it one night and called the studio at

a time when the music was playing so I could talk to the DJ. I told him thanks

for playing my new record and how important that is for me. I tried telling him

my name isn't Jeb Rodonti, it's Jim Rotondi. The DJ responded, “Man, I don't

know who you really are, but I'm looking at the CD right now and it says Jeb

Rodonti.”

GC: [laughs] Ok Jim, or should I say Jeb Rodonti, Ill be sure

to spell your name right….

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.